| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Panorama del Terzo di Città dalla Torre del Mangia

|

|

Piazza del Campo, visto dalla cima di Torre del Mangia

|

|

Capitoline Wolf in front of the Compleso Santa Maria della Scala

|

Siena Duomo | The Mosaic floor and the Porta del Cielo

Civic architecture and political ideology in the Republic of Siena, 1270 - 1420 by Grossman, Max Elijah, Ph.D., COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, 2006 | www.gradworks.umi.com

A study of Sienese civic architecture, from its inception at the beginning of the fourteenth century, during the regime of the Nine Governors, through the second decade of the fifteenth century, when the Republic reached its maximum geographical extent. Chapter Two analyzes the unique historical circumstances of the foundation of Siena, which was the only major city in Tuscany that did not exist in antiquity. The fact that it was founded in the "Dark Ages," and not during the glorious Etruscan or Roman civilizations, greatly influenced the designers of the civic style, who, inspired by republican philosophers like Tolomeo da Lucca, sought to instrumentalize their creation in order to revise the history of the city and proclaim its ancient origins.

Art in Tuscany | Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government

The frescoes on the walls of the Room of the Nine (Sala dei Nove) or Room of Peace (Sala della Pace) in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena are one of the masterworks of early renaissance secular painting. The "nine" was the oligarchal assembly of guild and monetary interests that governed the republic. Three walls are painted with frescoes consisting of a large assembly of allegorical figures of virtues in the Allegory of Good Government. In the other two facing panels, Ambrogio weaves panoramic visions of Effects of Good Government on Town and Country, and Allegory of Bad Government and its Effects on Town and Country. The better preserved "well-governed town and country" is an unrivaled pictorial encyclopedia of incidents in a peaceful medieval "borgo" and countryside.

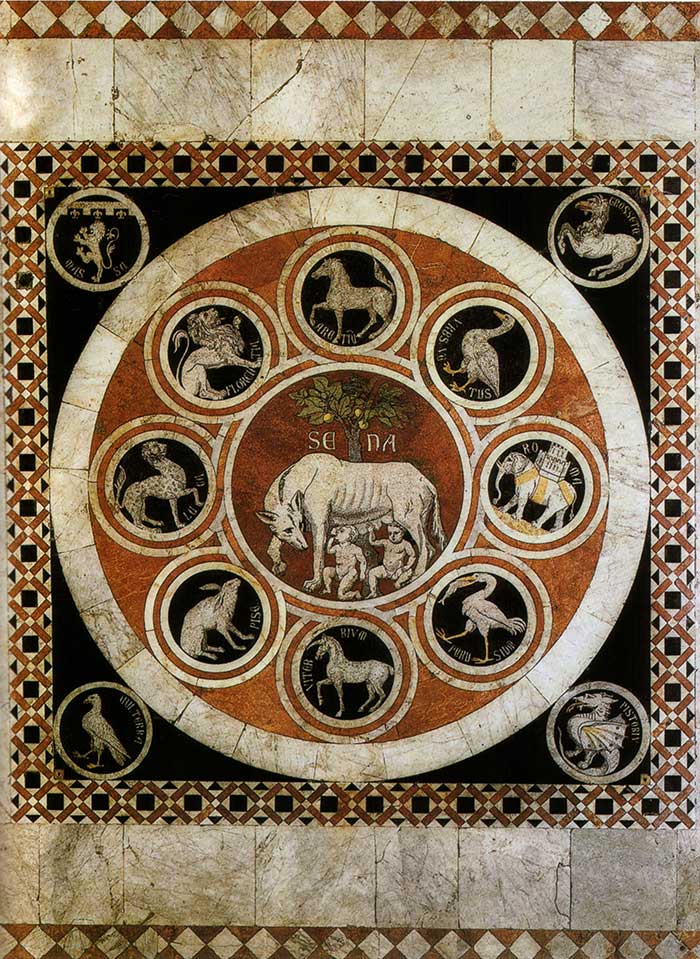

[1] The marble pavement of the Duomo of Siena is one of the most ornate in all of Italy. If the facade, columns and ceiling aren't enough to impress you, have a look down at the wonderful array of 59 etched and inlid marble depictions which were constructed between 1372 and 1547. They portray a large number of subjects including sibyls (oracle prophetesses of ancient Greece and Rome), scenes from Sienese history and various biblical scenes. The panels are attributed to the artists Domenico di Bartolo, Matteo di Giovanni, Pinturicchio and especially Beccafumi. A number of them are always on display, others in the transept are covered and only exposed for a few weeks during the Palio season.

The earliest scenes were produced by using the graffito technique (see main picture) which included drilling tiny holes and scratching lines in the marble and filling these with bitumen (a mixture of organic liquids which form a thick, black soluable substance) or mineral quick (a similar substance). Later works were produced by using black, white, green, red and blue marble intarsia (inlay).

The uncovered floor can only be seen for a period of six to ten weeks each year, generally including the month of September. The rest of the year, they are covered and only a few are on display. The earliest panel was probably the Wheel of Fortune, laid in 1372 (restored in 1864). The She-Wolf of Siena with the emblems of the confederate cities probably dates from 1373 (also restored in 1864). The Four Virtues and Mercy date from 1406, as established by a payment made to Marchese d'Adamo and his fellow workers. They were the craftsmen who executed the cartoons of Sienese painters. The first known artist working on the panels, was Domenico di Niccolò dei Cori, who was in charge of the cathedral between 1413 and 1423. We can ascribe to him several panels such as the Story of King David, David the Psalmist and David and Goliath. His successor as superintendent, Paolo di Martino, completed between 1424 and 1426 the Victory of Joshua and Victory of Samson over the Philistines. In 1434 the renowned painter Domenico di Bartolo continued with a new panel Emperor Sigismund Enthroned. The Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund was popular in Siena, because he resided there for ten months on his way to Rome for his coronation. Next to this panel, is the composition in 1447 (probably) by Pietro di Tommaso del Minella of the Death of Absolom. The next panel dates from 1473: Stories from the Life of Judith and the Liberation of Bethulia (probably) by Urbano da Cortona.

In 1480 Alberto Aringhieri was appointed superintendent of the works. From then on, the mosaic floor scheme began to make serious progress. Between 1481 and 1483 the ten panels of the Sibyls were worked out. A few are ascribed to eminent artists, such as Matteo di Giovanni (The Samian Sibyl), Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi (Hellespontine Sibyl) and Benvenuto di Giovanni (Albunenan Sibyl). The Cumaean, Delphic, Persian and Phrygian Sibyls are from the hand of the obscure German artist Vito di Marco. The Erythraean Sibyl was originally by Antonio Federighi, the Libyan Sibyl by the painter Guidoccio Cozzarelli, but both have been extensively renovated. The large panel in the transept The Slaughter of the Innocents is probably the work of Matteo di Giovanni in 1481. The large panel below, the Expulsion of Herod, was designed by Benvenuto di Giovanni in 1484-1485. The Story of Fortuna, or Hill of Virtue, by Pinturicchio in 1504, was the last one commissioned by Aringhieri. This panel also gives a depiction of Socrates. Domenico Beccafumi, the most renowned Sienese artist of his time, worked on cartoons for the floor during thirty years (1518-1547). Half of the thirteen Scenes from the Life of Elijah, in the transept of the cathedral, were designed by him (two hexagons and two rhombuses). The eight meter long frieze Moses Striking water from the Rock was executed by him in 1525. The bordering panel, Moses on Mount Sinai was laid in 1531. His final contribution was the panel in front of the main altar: the Sacrifice of Isaac (1547).

Art in Tuscany | The marble pavement of the Duomo of Siena

[2] 'Unfortunately for the Sienese, the most widely-known story of the foundation of Siena came from the twelfth-century Policraticus by John of Salisbury, an Englishman, and it linked the Sienese not to the Romans or any other native Italic people—but to the French and the British. He claimed that Siena derived its name from its founding by a group of ancient Gauls called the Galli Senones:

"

In his twentieth book, Pompeius Trogus recounts that when the Senonese Gauls, soldiers of Brennus [leader of the Galli Senones], came into Italy, they exiled the Tuscans from their homes, and founded grand cities there: Milan, Corneto, Brescia, Verona, Bergamo, Trent, and Vicenza. And they built the city of the Sienese for those that were old or weak, and for their herdsmen. The truth of this is not only in the histories, but in a well-known tradition (which is therefore more reliable), that the Sienese seem more similar in the proportions of their limbs, the beauty of their faces, the fairness of their coloring, and their customs to the Gauls and Britons, from whom they can trace their origin." John of Salisbury (1844-55).

Sources: Siena: Romulus & Remus, Revisit | www. faculty.ncf.edu

[3] Photo by Petar Miloševic - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38856950

|

Tuscan Holiday houses | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| De open haard |

|

en de pizzaoven |

|

Zonsondergang metMontecristo en Corsica op de achtergrond

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early morning light at the private swimming pool at Podere Santa Pia

|

|

A bigger splash in swimming pool at Podere Santa Pia, southern Tuscany

|

|

A bigger splash in the pool, Podere Santa Pia, Castiglioncello Bandini, Cinigiano, Tuscany

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, situata sulle splendide colline del valle d'Ombrone nel cuore della Maremma

|

| Siena and the Palio | Myths, Legends, and the Linear Palio (1000-1300)

Quite when did the Palio begin? The question appears every summer in the thoughts of all Sienese. If no precise date exists, an answer still can be found: the Palio is as old as Siena, running through the city's myths, legends, and history.

Over the centuries it came to be the distinctive element of the city, many would say to the point of becoming the fourth dimension of the city's reality, the indispensable, the primary mechanism moulding the city, giving meaning to all that the city is and does. The Contrada shapes the strong social identity of the Sienese and the Palio gives them a model of how things are to be done. Even in politics, says a local proverb, the Palio is run all year long.

Siena was an Etruscan city, modest but well-connected to the major centers of Etruria: Fiesole and Chiusi, Cortona and Volterra. Many have pointed out fascinating analogies between the first Palios and the equestrian games of the Etruscans and earlier still of the Greeks. In Poggio Civitate, not far from Siena, there is a fragment of pediment, from the 6th century b.c., showing a series of horsemen lined up, riding bareback like today's jockeys and, like their modern counterparts, they are equiped with riding crops and hats, all set to run their Etruscan Palio.

Another myth of the race's origins - favoring Siena as born from the rib of Rome and founded by the fugitive sons of Remus - depicts those men reaching the fateful place after a great race, chased by the horsemen of Romulus. Senio and Aschio thus founded Siena at the end of a mythic “linear Palio.” The insignia of the new city was to be white and black after their horses and the clouds of smoke that rose from the two sites where they offered their sacrifices to the gods.

The Balzana (the old Roman insignia in black and white) remained the Coat of Arms of Siena, perhaps because, as Geno Pampaloni wrote, it is the perfect symbol of the extreme character of the city. It seems the irreducible opposition of white and black, yet the Balzana in fact presents the fusion of all colors in the white and their absolute absence in the black.

The same is true of the Palio: the Balzana is omnipresent as the insignia of the Municipality and as a sign of everything, reductio ad unum of the agreeable disagreement, of the seeming harmony between between Contrade which, with their individual colors and flags, are divided and oppose each other, set themselves apart and clash. But they refind each other and unite in the Balzana, like the Sienese people when they are happy to run into each other away from home or when they pit themselves against the rest of the world. The obsessively black and white marbles of the Cathedral, symbol to some of the glory and pain of the Madonna, render the building a kind of “sacred Balzana,” and thus the appropriate setting for the offering of candles, the benediction of the Palio banner, the Te Deum of victory, for the most intense and tumultuous moments of popular religiousness, which may be archaic in form, but fully heartfelt as an indispensable and ever-current part of the Palio rites.

It was in the church-square of the black and white New Cathedral in the 1200s that the insignia of the City-State was placed to mark the finish line of the race of the barb horses, the linear Palio which in previous centuries had been run through the tortuous city streets all the way to the old Cathedral, dedicated to San Boniface, as recorded in documents from the 11th century. When Siena became one of the richest and most cultured cities in Medieval Europe, the Palio was the sporting event and culminating moment that crowned and concluded the spendid annual festivals in honor of Our Lady of August, Virgin Mary of the Assumption, queen and patron of Siena and of its State. To her was the city dedicated and entrusted. The keys of the city were offered to her in the most critical moments of the city's history, from the eve of the Battle of Montaperti in 1260 to passage of the Front in 1944.

For the Festival of the Assumption Siena became an “open city.” Arrests were suspended; exiles could return and freely walk the town; goods and livestock poured into the marketplace; streets came alive with musicians and minstrels, mimes and jesters who entertained the crowds; acrobats and strongmen, teeth-pullers and healers, trinket-sellers and harlots, wine-merchants and vendors offered their wares and their services. The city displayed tapestries and flags, decorations, festoons and garlands: in 1329 the City-State ordered 600 of these to be made. In 1378 monies were spent on fireworks, then considered a marvel.

The culmination was the offering of candles and tributes in the Cathedral, a religious and political rite, an act of Sienese devotion to the Madonna and of subordination to the vicars, the leaders of the City-State. The collective oath of allegiance was its own precise ritual: a scroll from 1200 describes it, referring to an article in an older statute, since lost. The quantity of fine waxen tributes to be offered varied according the importance of whoever made the offering, but all citizens (from 18 to 70 years old) were dutibound to make offerings, as were all institutions of Siena and its State, most notably the Municipality which offered a gold-leafed and painted candle, as it does today. In the years of the greatest splendor, the Sienese who packed the Cathedral watched as, before their Madonna to whom vows were offered, there kneeled former enemies, now become fellow citizens: the Counts of Scialenga and the Counts Gherardesca, the wise Aldobrandeschi and the Guidi, legendary warriors. The wax that the workers of the Catherdral amassed beneath the dome reached a weight of 30,000 lbs.,then redistributed to the small churches and parishes of the diocese, representing the ancient paradigm of the ritual donation, with the symbolic obligations of giving, receiving, and reciprocating. In the words of a saying much cherished by Boccaccio, “The Church is like the sea, from everyone it takes and to everyone it gives.”

The Municipality played an analogous role in the secular aspects of the festival. Prisoners to be freed from the dungeons were drawn by lot, as were the names of virtuous and needy maidens whose dowries were provided for “at the public expense.” Public reconciliations between factions and families gave relief to feuds among the citizenry. Food and drink was provided for all. In the act of submission of Montelaterone (1205), the Municipality committed itself to giving victuals to anyone who brought a tribute of fine wax to Siena. This was the first documentation of the custom that was to continue in the banquet offered by the Signoria and today in the dinners on the eve of the Palio sumptuously laid out on the streets for thousands of celebrants. In the period of the “culture of hunger” - experienced by even the most splendid cities such as Siena - the festival was a moment of liberation from the strict daily rations of bread and wine. The city found, gave, and abounded in food and drink for everyone, wines and meats, cookies and blancmanges, the precursors of cavallucci and riccarelli, copate and panforti, the Sienese delicacies of today.

To organize the Palio the Municipality annually nominated the Deputees of the Festival, mentioned in records from the 1300s with tasks and status greater than those of today. Running in the Palio were the nobles and notables on their battle-horses: the medieval games were mimed battles, training for war. The linear track ran from outside the walls all the way to the Cathedral, from the outlying fields to the streets, over muddy roads like Pantaneto to the marble of the Cathedral, from the country to the city. The prize was the Pallium, a long piece of precious cloth, sometimes stitched in vertical bands, stuffed with hundreds of vaio fur pelts. The Pallium later gave its name to the race and then to the festival. This linguistic fact underlines a tie between sign and context, symbol and ceremony, meaning and the meaningful.

From the start the race was sensational and dramatic, full of accidents and events.

The oldest document recording the Palio, from 1238, deals with Palio justice. A fine of 40 farthings was to be paid to Ristoro di Bruno Ciguarde because “running in the Palio and having arrived last, he did not take the pig, the derisory prize assigned by the regulation to the most losing of all the losers” (at that time, last place; today, 2nd place). Such a “purge” helped define victory and defeat, establishing hierarchies ofwinners and losers, dictating the symbolic order of homo ludens.

Another sign of the times lies in the Constitution of 1262, in which it is decreed that the qui current eques, the participants of the Palio, the noble jockeys of that era, could not be prosecuted for homocide or injury occurring during the race, because “predicta maleficia non committerint studiose” - “they didn't do it on purpose.” What was asked of jockeys was above all a theatrical show of honesty.

These first Palios were an affair of the noblemen. The Contrade participated, instead, in the crude games in which masses of contestants opposed each other on the basis of territory (eg.,La Città against Camollia and S. Martino). Siena was born plural, on three hills. The three primeval castles expanded into Thirds (Città, Camollia, S. Martino) growing until they met and almost dictated the site of the Campus Fori, the Piazza del Campo. The Contrade grew up within this 3-way partitioning, an Indoeuropean matrix there since the Etruscans and which in Siena stubbornly refused the 4-way partitioning laid out everywhere by the Romans.

The oldest documentation of the Contrade lies in the regulations of 1200, prescribing that all citizens were to bring a candle to the Catherdral cum hominibus sue contrate.

Historian Andrea Dei affirms that the Sienese “began to create companies in the city of the Contrade” in 1209. Contrada originally meant “a main inhabited street,” then “neighborhood,” and finally the association of a district's inhabitants.

Giovanni Cecchini, authoritative writer on Palio historiography, notes, “the Contrada, as a territorial and administrative district, is as old as the city itself.” E. William Heywood, an important Palio historian, adds, “For the past 400 years the Contrade have been the distinguishing characteristic of life in Siena, the equivalent of which can be found in no other Italian city.”

The Contrade used to be far more numerous. After the Plague of 1347, their number was reduced to 42. They took their names from streets, gates, fountains, churches or illustrious families within their territories. They fulfilled religious, administrative, military, and recreational functions. The head of the Contrada was the Sindaco, the Mayor, who was directly answerable to the Podestà, aided by popularly elected counsellors. The Contrada was subject to taxes, it ran its own police force, saw to the upkeep of streets, and carried out other services for the public good.

[From Myths, Legends, and the Linear Palio (1000-1300) | www.comune.siena.it] |

|

|

![]()