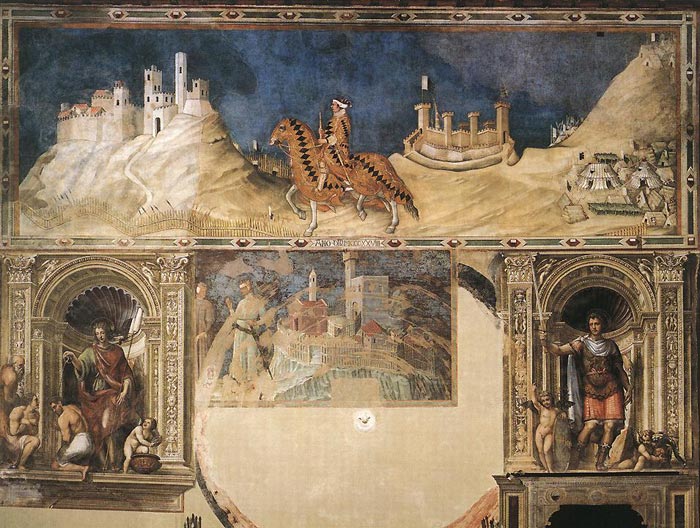

Simone Martini | Guidoriccio da Fogliano in Palazzo Pubblico, Siena |

| Simone Martini was born in 1284. Though little is known of his artistic origins (Vasari gives Giotto as his teacher) he appears as a fully developed master when he painted the Majestas in the Sala del Consiglio of the Siena Town Hall in 1315. In 1328, Siena, under the leadership of its war captain, Guido Riccio da Fogliano, besieged and captured the nearby town of Montemassi. As was custom, the Sienese government soon after (1330) commissioned a picture of the recently captured town to be painted by Simone Martini in the town hall of Siena, the Palazzo Pubblico. Because the Guido Riccio fresco portrays the castle of Montemassi on its left side and includes the depiction of other supposed circumstances surrounding that castle's capture, art historians have assumed that what exists today is Simone's original.[1] Originally hired by wealthy Italian city states to protect their assets during a time of ceaseless warring, the Condottiere of the Italian peninsula became famous for his wealth, venality and amorality during the 14th century. The Condottieri's pursuit of profit meant they were prepared to change sides for the right price, even during battle, and they prospered, becoming both powerful and rich in the process. Leaders such as John Hawkwood, with his famous 'White Company', became major political figures. Once at the peak of their power, they often worked together to protect their comfortable position by staging a number of visually impressive but almost bloodless battles, thereby avoiding the real thing. It was because of this, and their reliance on medieval tactics and weaponry, including grand armoured knights, that they were eventually wiped out or dispersed by the more modern armies. |

More than other paintings of its supposed era, the Guido Riccio fresco inspired elaborate and eloquent analysis. One can read about how the famed Simone Martini fused realism, fantasy, and pictorial imagination in a truly exceptional manner. He provided the viewer not only with the facts about a specific siege-in this, it is emphasized, the painter was especially accurate-but with the universal truths about warfare, its destruction, and its desolation. All of this, we are told, Simone presented with a refined elegance that is unique to his special sensibilities. In short, the Guido Riccio became an exquisite example of fourteenth-century taste and a testimony to Simone's genius.[1]

|

||

|

||

Simone Martini, Equestrian portrait of Guidoriccio da Fogliano, 1328-30, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena |

||

Military glory juxtaposed heavenly glory, where the mounted knight is shown cloaked in his tabard, embroidered with all the insignia of the da Fogliano family, his horse liveried in the same style. The figures are outlined, avoiding contact with the surrounding landscape - the Montemassi castle to the left, the wall of the besieged hill town above and below, the Battifolle castle with its siege towers and the Sienese military camp low on the left, with tents and agricultural fields. The painting’s unusual subject, coinciding with the arrival of chronicle painting, is arranged to support contemporary political reality. This new style of painting portrayed society as worthy of artistic attention, not merely as an intermediary between the human and the divine. Simone Martini’s authorship had been taken for granted for centuries but, from the 1980s, his fresco was at the centre of an argument regarding its authenticity. Long debates between important critics such as Briganti and Zeri called the attribution of the Guidoriccio into doubt. Whatever one believes, it can be confirmed that the painting – or at least its original parts - is of the highest stylistic element and technical quality. The skills needed are clear signs of Simone Martini’s hand. Below the Guidoriccio, Simone Martini - there is another fresco with a similar theme. This was painted around twenty years earlier by an exceptional hand, showing Due personaggi e un castello – Two Characters and a Castle. The fact that the work was soon covered with a layer of plaster makes it impossible to attribute it to any particular tradition in painting. A heated debate has enveloped this fresco too. Some refer to it as the last of Duccio’s works. His work as a fresco artist was little known until recently, but is now identified in numerous examples from Siena and its surrounding. Another hypothesis, again by Zeri but in contrast to what he has said about the Guidoriccio, is that the painting is by Simone Martini. Less likely are the proposals that the work is by Ambrogio Lorenzetti or Memmo di Filippuccio. The protagonist could be the podestà or a citizen of the Republic of Siena in the act of capturing a castle. Simone Martini. The iconography once again refers to military glory and Siena’s expansionist aims. This fresco was probably painted over, as were many others showing the lands and castles conquered by Siena, to make way for the Mappamondo by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. This was an elaborate rotating disc, a large wooden wheel covered in cartapecora – parchment. Unfortunately lost three centuries ago – though a vague description exists – it contained an image of the city of Siena in its centre, surrounded by its associated lands and, in the background, all other lands known at the time. Nothing remains except the imprints of its attachment to the wall, the hole for the central pin, and of course the fact that it gave the room its name. Below the Guidoriccio, Simone Martini - in 1529, Sodoma painted two of the city’s patron saints: San Vittore and Sant’Ansano, both perfectly preserved.[1]

|

||

|

||

|

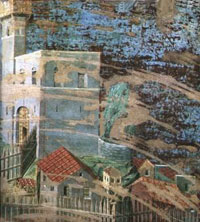

Unknown Master (first quarter of 14th century), Castle on a Hill, 1300-25, fresco in Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

|

||

| For Gordon Moran, Michael Mallory, the newly discovered fresco depicts Arcidosso, which, along with Castel del Piano, is documented as having been added to the castle series in 1331. Its structures and landscape resemble presentday Arcidosso exceptionally closely, and included as an additional identifying feature is a three-branched tree that leans out from the base of the keep, a device found in many of Arcidosso's town seals. Logically, the figure with the sheathed sword is Siena's war captain at the time of Arcidosso's acquisition accepting the submission of the other figure, the castle's count, who removes his gloves in a gesture of fealty. Inasmuch as the newly discovered fresco originally extended further to the left and was subsequently covered by the painter Sodoma's depiction of Saint Ansanus around 1530, it could well have included a representation of Castel del Piano, as we would expect from the document of 1331. The identification of the newly discovered fresco as Arcidosso had and continues to have an explosive impact on the whole Guido Riccio controversy. Arcidosso was painted in 1331, over a year later than the presumed date of origin of the Guido Riccio. How, then, can a later fresco lie partially beneath an earlier one? If the newly discovered fresco does, indeed, represent Arcidosso, the art world faces a truly ironic situation. Because the castle is recorded as having been painted by "Simone," supposedly Simone Martini, it would be the newly discovered fresco, and not the famous one, that is actually an original by the renowned artist. The piece de resistance is that the recently discovered, real Simone Martini fresco actually might include a portrait of Guido Riccio da Fogliano; he was Siena's war captain at the time of Arcidosso's acquisition and would logically be the warrior taking possession of the castle. r Gordon Moran, Michael Mallory, and others, the newly discovered fresco depicts Arcidosso, which, along with Castel del Piano, is documented as having been added to the castle series in 1331. Its structures and landscape resemble presentday Arcidosso exceptionally closely, and included as an additional identifying feature is a three-branched tree that leans out from the base of the keep, a device found in many of Arcidosso's town seals.[1]

|

|

|||

|

||||

SImone Martini, Guidoriccio da Fogliano all'assedio di Montemassi (detail), 1328-30, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

|

||||

| [1] Gordon Moran and Michael Mallory, The Guido Riccio controversy and resistance to critical thinking, Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991), Vol. 11, Iss. 1 [1991], Art. 5 For Gordon Moran and Michael Mallory, the famous Guido Riccio is 'an elaborate restoration, in effect, a fanciful re-creation, of works, or at least of fragments of works, from the fourteenth century. While some of these actually were painted by Simone Martini, the new Guido Riccio fresco bears little if any resemblance to the originals. They were smaller and probably included no horse and rider. Not only does the Guido Riccio distort our view of what a genuine fourteenth- century work might look like, but it may actually be covering the still-extant originals that it seems to have replaced.' [pp.2-3] |

Een werpmachine met buidel voor zware stenen, ingezet om een van de toegangspoorten te verdedigen, Guidoriccio da Fogliano door Simone Martini

|

|||

| Simone Martini (c. 1284–1344) was an Italian painter born in Siena. He was a major figure in the development of early Italian painting and greatly influenced the development of the International Gothic style. It is thought that Martini was a pupil of Duccio di Buoninsegna, the leading Sienese painter of his time. According to late Renaissance art biographer Giorgio Vasari, Simone was instead a pupil of Giotto di Bondone, with whom he went to Rome to paint at the Old St. Peter's Basilica, Giotto also executing a mosaic there. Martini's brother-in-law was the artist Lippo Memmi. Very little documentation survives regarding Simone's life, and many attributions are debated by art historians. Simone was doubtlessly apprenticed from an early age, as would have been the normal practice. Among his first documented works is the Maestà of 1315 in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. A copy of the work, executed shortly thereafter by Lippo Memmi in San Gimignano, testifies to the enduring influence Simone's prototypes would have on other artists throughout the 14th century. Perpetuating the Sienese tradition, Simone's style contrasted with the sobriety and monumentality of Florentine art, and is noted for its soft, stylized, decorative features, sinuosity of line, and courtly elegance. Simone's art owes much to French manuscript illumination and ivory carving: examples of such art were brought to Siena in the fourteenth century by means of the Via Francigena, a main pilgrimage and trade route from Northern Europe to Rome. Simone's other major works include the St. Louis of Toulouse Crowning the King at the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples (1317), the Saint Catherine of Alexandria Polyptych in Pisa (1319) and the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus at the Uffizi in Florence (1333), as well as frescoes in the San Martino Chapel in the lower church of the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi. Francis Petrarch became a friend of Simone's while in Avignon, and two of Petrarch's sonnets (Canzoniere 96 and 130) make reference to a portrait of Laura de Noves that Simone supposedly painted for the poet (according to Vasari). A Christ Discovered in the Temple (1342) is in the collections of Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery. Simone Martini died while in the service of the Papal court at Avignon in 1344. |

Giorgio Vasari, Simone Martini |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Monte Christo |

||

|

||||

Montalcino |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

|||

|

||||

Visitors of Podere Santa Pia are are greeted by a stunning view of the wood and farm lands that carry to the western shores of Tuscany |

||||